Janush Panchenko: from life under occupation to freedom in Europe

This is a new remarkable story about the fate of a young Roma in the conditions of war – from occupation, escape to freedom. The interview with Roma activist, historian, ethnographer Janush Panchenko from Kakhovka.

- Standard question - how did it all start for you?

- On the first day of the Russian invasion, I woke up at five in the morning, the whole house was shaking. Explosions woke me up, I opened my eyes and lay there, waiting for what would happen next, the explosions began to repeat. Half an hour later, I got a message that the explosions had taken place in nearby Nova Kakhovka. I called my brother, who lived in Nova, he instantly picked up the phone, and such a quick answer at 5.30 in the morning alerted me. I asked him about what was happening in their town, he answered me briefly and somehow sharply: “The war has begun, we are going to the bomb shelter, then I will dial.” Two hours later I went to Nova Kakhovka to fetch my brother and his family. On the way, I saw military vehicles without flags, with the swastika “Z”. I didn’t know then what those signs meant. And the equipment was so old, I thought it was our local military. When we returned, with my brother’s family, to Kakhovka we again saw huge cars, tanks, the caterpillars of which crumbled the asphalt. It was creepy because I had never seen so much military equipment before. We were driving along the highway in the right lane, and they were moving on the left towards us. We drove and approached each other, I did not know how to behave in this situation, and decided to slow down the speed of my car to a minimum, in the end we successfully drove home. Arriving home, I turned on the TV and then I realized that the swastika “Z” marks the Russian occupation army. But even after that, I did not take it seriously, I probably did not want to realize the seriousness of what had happened.

Five days later, I again went to Nova Kakhovka, but on a different road and on the way I saw civilian cars, some of them were simply burned and scattered all over the road, like toys. Looking at these cars, I realized that no one was alive there. At that moment, I realized that it was the Russians who simply shot down the cars of civilians who, on the first day of the Russian invasion, left the town in a panic. And I thought that two days ago we could have been driving along this street, but we were lucky to be alive. The occupiers that we met did not shoot civilian cars, and those that these people met killed everyone. At that moment, I became aware of the horror that was happening. And I no longer had the opportunity to doubt anything.

- You said that you live in Kakhovka, tell us how the occupation took place in the early days?

- Yes, I live in Kakhovka. The first weeks I did not meet the Russian occupiers, except for the case that I spoke about. We heard a lot of explosions, but I did not see any soldiers or military equipment. Therefore, the occupation in the first days was not particularly felt, our local Ukrainian authorities continued to work, everyone was in their places. The occupiers were mainly located in the neighboring Nova Kakhovka, which I also spoke about, they did not call in our town, at least I did not meet them.

- And why?

- Kakhovska hydroelectric power station is located in Nova Kakhovka, probably, it was more important, so they were mostly located there. About in the fourth month of the occupation, there were already a lot of Russian soldiers with us, the town was full of them. Periodically, they drove along my street.

- Did the Russian soldiers have any intentions to break into your house? Or to one of the Roma?

- There were, in Vysokopіll’a, Velyka Oleksandrivka, the invaders plundered several Roma houses, this was already known in May. Later, there were many such cases in Kherson, and then in Kakhovka, Berislav. They were mainly looking for money and gold, but they carried out everything they could, for example, equipment often. The invaders mainly looted the houses left by the owners, but there was a case when they looted the house where the family lived, they beat the family members.

They also occupied the Roma youth center in Kakhovka, but there was nothing to rob there. Since we took everything of value from there in the first days. On May 9, they broke down the doors to our center, and in June they already occupied the premises. Since that time, I periodically saw the Z-men near the center when I passed by it. But I was glad that there was nothing of value inside.

- I don’t understand why you didn’t leave right away? I myself am from Transcarpathia, and we are far from Russia, Thank God, but when they heard about the war, a lot of people left everything and left. What plans did you have?

- Even before the war, we said that in the event of a Russian invasion, we would leave for Lviv, but when the invasion began, there were doubts whether to go or not, plus there were shelling along the way, many people died on the way, we decided that it would be safer to stay at home. On the first day, we started calling relatives to leave and take the children with us. We called one, and then the second ... in the end, we decided to get together with several families, to be in the same house. Then several families came to us, we lived together for about a month, 12 people.

- And what kind of situation did you have when you lived together, how did you feel?

- We were all so relaxed. I felt safer, I think everyone felt that way. Sometimes we were in the house, and sometimes we went down to the basement, mostly at night. We slept dressed, so that in case of emergency, we could quickly leave the house and go to the shelter. But, it was hard, because out of 12 people in the house, 3 were children. It is very difficult for children to get up at night, get ready, go somewhere.

At that moment, an elderly Roma woman lived with us, she was 76 years old, she unconsciously called the Russian soldiers “Germans” and prayed every day with the children, and those were very sensual moments.

We lived like this for about a month, at first it was all terrifying: shots, explosions, fighter flights, and then not. People get used to everything and you get used to it too. A month later, one family returned home, then we lived with five of us.

- Did all the Roma stay in Kakhovka or were there those who left right away?

- The first wave of departures was at the very beginning of the war, the Roma, out of panic or shock, simply went into the unknown, mainly to Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, sometimes to the Dnipro. This lasted for about a week. After a week of war, people preferred to stay at home.

- Were there any cases on the part of the Russians in relation to the Roma?

- The first case was when a Roma guy disappeared, I’m not even sure that he is an adult, he is 17-19 years old. His grandmother called me and said Anton (name changed) disappeared, he has been gone for a week. We did not know where he had disappeared, although everyone understood where one could disappear in such conditions. In total, he was gone for 20 days, during which time there were many rumors that he was killed, that someone saw him killed, and the like. But then his family called me and said that Anton was already at home. He was beaten, tortured and abused. As I learned later from him, the Russians stopped him on the street, and he did not have any documents with him and they took him away for identification. But in fact, he turned into a worker for them: he dug holes, buried the corpses of dead people and the remains of their bodies...

Then there was the case of the capture of several more Roma for suspicion of helping the Ukrainian army. These cases were “on hearing” among our Roma, all this influenced the departure of people from the Kherson region.

- Were you free to leave Kakhovka?

- Until May, I think so. Although there were difficulties, sometimes you had to wait a long time on the front line. My mother and I also planned to leave through Vasyl’ivka to Lviv, then Ivano-Frankivsk, we also thought about Odesa. We wanted to take another family with us. In this family, a Roma man was after a stroke and he needed pills for the journey. There was nothing in the town at all, no drugs. A humanitarian catastrophe, you couldn’t even find something primitive. Volunteers were supposed to bring pills, and we waited a long time for them. But in the end, this family decided to stay. Then my car broke down, and it was very difficult to buy some spare parts, they were not in the town either. Then my friend found the necessary parts in Kherson and brought them to me, and exactly on the day he arrived from Kherson, the Antonivskyi bridge was destroyed, that is, it was the last day when it was possible to drive from Kherson to Kakhovka at all. In general, because of this, everything was delayed, at a certain period it became even more difficult to get to the territory of free Ukraine. People who were driving their own cars waited 2-3 weeks in line in the gray zone. Although some of my brothers still managed to get to Lviv, but in the end they said: “If we knew how and what it would be, we would not go through Vasyl’ivka”. In addition, we provided food support to the local population, mostly Roma, the situation was very difficult. It seemed to me that I could not leave so early, several families called me every day and asked for at least some minimal food assistance. Some people didn’t really have anything to eat.

- This was before the occupation of the entire territory of the Kherson region. What is the situation now in Kakhovka on the left bank, since you are still under occupation?

- Now it is generally impossible to leave Kakhovka for the territory of free Ukraine, since all the bridges have been blown up. Only in the Crimea is possible, but it always becomes more difficult.

- How did you leave Kakhovka?

- We left through the Crimea. Before that, my relatives, friends, most left. I was left alone in Kakhovka from Roma people, I mean, people from my circle of friends. Plus, the occupiers occupied the youth center, I felt that they might soon come for me, my mother was very afraid of this, and asked me not to write anything on social networks about the occupiers, and to stay out of the public eye, but I couldn’t help but do it, I was very hurt and painful for my town and its people.

- You wanted to be the first to leave, but you were the last to stay ...

- (Laughs) Yes, I wanted to be the first, but I stayed the last. On July 25-26 there was heavy shelling, some kind of strong explosion. I can’t say exactly what it was. We were in the basement. We have huge iron gates and they beat so hard from the wave of the explosion, beyond words. It was so creepy… (silent).

- At this point, did you decide to leave?

- You can say yes. I sat and thought why I am here? I rethought everything and considered that there is no reason to stay here. At this point, we decided to leave.

- Did you leave at the same moment?

- But not at once. Before leaving, I still had to prepare for the filtration camp in the Crimea. The first checkpoint was in the Kherson region, near Chaplynka. There was a small Russian checkpoint on the road, there was an occupier in a cap with the inscription LPR (Luhansk People’s Republic). He stood in the middle of the road with a machine gun and gestured for me to stop. I stood on the road beside him. He was drunk, his behavior was impudent and aggressive. He started yelling that I got up wrong, and when he opened his mouth the vile smell of fumes “poured” on me. I tried to talk to him calmly to soften his tone.

- What did you say to him?

- He said: “You didn’t get fucked here. War. You need to become exactly on command, then fuck you”. I tried not to show that I was scared. I tried to answer normally and not argue with him. But inside I was stressful, actually. We had a dialogue for three minutes. As a result, he slowed down the pace and began to communicate more adequately. Then he seemed to begin to justify his behavior, saying that he was yelling for my own good: “There are tanks, armored personnel carriers driving, they fly, they demolish cars on the highway, they don’t stop”. While he was speaking, a combat vehicle of the invaders swept by at speed near us. He continued: “You see, they run non-stop, if you stood a little in the wrong place, they would run over you and would not even notice”. After that, he looked through our things in the trunk and let us through.

We reached the so-called Crimean border, where we stood for 8 hours, waiting. As a result, we ended up on the territory of the checkpoint, it was near Armyans’k. At the very border, the invaders organized a filtration camp for men entering the territory of Crimea. So to speak, they conduct interviews with men, check the phones, “punch through” the personality. It looks like they have some kind of database where they check information about a person. As I said, I prepared for the trip, because I heard from those who passed earlier that phones are checked quite thoroughly, even deleted files are restored. Therefore, three weeks before the trip, I bought a new phone, and left the old one. I deleted my pages on social networks, various publications on the topic of the war, deleted everything I could as much as possible and often thought about the alleged questions addressed to me at the border. Prepare for a possible dialogue.

And now, it’s time for the filtration camp. I entered the territory, there were many men from Ukraine sitting on the street, and there were also about four conditional offices. Guys were called into these offices one by one and interviews were conducted there. I was invited to one of these. At first, I felt quite confident in myself, but then, during a conversation with the occupier, I cannot explain this feeling, it became morally difficult for me to talk to him. He did not say anything insulting and rude to me, but for some reason it was psychologically and morally difficult for me to answer him. I felt like I was being pressured, it became increasingly difficult for me to answer his questions. I felt that the pressure was affecting me and I was confused, it became more and more difficult for me to logically connect my previous answers with new ones. When choosing answers to his questions, I immediately tried to understand what question would arise after I voiced the answer to him, and in advance I tried to come up with an answer to a potential new question.

Later, he took my passport and started entering my data into some program, after that he showed me my photo on his phone and asked:

- Is it you?

“Yes, I am”, I said.

He started looking at his phone again and reading my biography:

- “He worked at school number 6, he worked at the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation. Is this about you?”

“About me”, I said.

Then he began to ask whether I served in the army, whether I have relatives or friends in the Armed Forces of Ukraine or the territorial defense.

It was difficult for me to say “there is no one”, because it is not true, my friends are in the territorial defense, my supervisor is in the territorial defense, my brother is in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and my neighbor is also there. I replied that I do not know who is doing what at the present time, maybe there is, but maybe not.

“Everything is clear with you, come out, leave your phone and passport”, he told me.

I went out into the street and began to worry, because throughout the entire period of my life in the occupation, I wrote a lot on the net against the Kremlin and what it is doing to the people of Ukraine, besides, my friends and brother in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. It will not be a problem for the Russian border guards to find grounds for my detention. I sat like this for an hour, during that hour I suddenly remembered that I hadn’t deleted all the anti-Russian publications from social networks, and the more I thought, the more I began to recall compromising information about myself. I worried. I sat and thought: “Damn, I’ve been preparing for this trip for two weeks, and in the end it turns out that in two minutes you can collect a lot of compromising evidence on me.” After an hour of waiting, the invader came out and said:

- Panchenko Janush?

I approached him, he gave me my passport and phone, I took my things and asked:

- Can I go? – Having received nothing in return, I decided that I could go on. I got back in my car, and I was incredibly happy (laughs).

- What were your plans next?

- One night we spent the night in a hotel in Kerch, the administrator turned out to be a “vatnik” woman, I started arguing with her a little, trying to explain the truth, but it was useless, at one moment I stopped responding to this topic, besides it was not very safe.

The next morning we had a long road through Russia to the civilized world, to Europe. We drove for a long time, 1,900 km somewhere from Kerch to the border of Russia and Latvia. The road is hard, plus the experience that there will be problems in Russia, because we were driving with Ukrainian license plates. On the road, we often met Russian military equipment that was driving towards Ukraine, there were especially many in the Krasnodar Territory and the Rostov Region, we cursed every car, saying: “So that you crashed”, “Drive, our people are already waiting for you there” and all that (laughs).

This, by the way, was August 2, the day of the Russian Nazi, or in other words, the day of the Russian Airborne Forces. On this day, in general, a lot of civilian cars drove, with the swastika “Z”, the inscriptions “For Russia!”, with the flags of the Airborne Forces and the Russian tricolor. We were driving along the highway, and the flag of the Airborne Forces was lying on it, apparently someone flew off the car. It was lying on the road and all Russian cars drove around him, as if as a sign of respect, I guess. And we turned the car on purpose so as to run over it. I remember that because it lifted our spirits at that moment.

Finally, we reached the Russia-Latvia border, the “Burachki” border checkpoint (Pskov region). There were seventy cars there, mostly with Ukrainian license plate numbers. The line moved so slowly that we spent 36 hours there. We spent almost two nights in the car. During this time, I already managed to get to know the people standing next to us in line. There were a lot of people from the Luhansk and Donetsk regions.

In the end, we waited for our turn. And when I arrived at the checkpoint, I understood why everything was taking so long. Car filtering again. European and Russian cars passed faster, there were separate rows for them. But they put all Ukrainian cars in the first two rows, and the situation did not change for us. Because the rows with Ukrainian cars did not work, practically.

To this whole difficult road, there is still a border with a wait of up to 40 hours, just awful. There was no water, no conditions. In front of me there was a family from the Donetsk region with a one-year-old child. And they were not released from Russia, the guy was not only upset, he was “killed”... He traveled such a road... I sympathized with him very much, because I understood what road he had traveled with a small child. And I thought: “Now the same thing will happen to us”. Already I began to build in my head a route to return home. But in the end we were let through. Then we incredibly quickly crossed the Latvian border, in about 30 minutes. When we stopped at the Latvian checkpoint, they gave us leaflets with an inscription in Ukrainian: “Welcome to Europe, we understand that there is a war in your country and we will make every effort for your victory and for you to feel comfortable in Europe”, it was also a pleasant and inspiring moment.

- What is the current situation in Kakhovka? Have a connection with someone?

- It had been bad in Kakhovka, but after their referendum it got even worse. I called relatives at home. Now there is complete chaos. They enter houses and rob everyone. A lot of Roma houses were occupied by the invaders. Many Roma began to be taken prisoner for any reason. On the street, cars are taken from people under the threat of being shot, but this is not only among the Roma, among everyone.

- Having left your occupied hometown, what can you remember now? What comes to your mind?

- Rallies against the occupation. This is not a transferable atmosphere, everyone is united and supports each other. I participated not in all, but in many rallies. People were not familiar, but they all empathized together. The last rally I was at, Russian soldiers came with machine guns, dispersed everyone and threw a light-noise grenade. It was without a charge, but still there was an explosion ... Someone was injured, it was scary, you know... (silent).

- Did the Roma of Kakhovka sympathize with Russia before the war?

- The Roma are the same as the rest of all Ukrainians, there was a small part that sympathized with the prospect of living under Russian control. But in the course of the development of Russian aggression, the strengthening of occupational measures, sympathizers became less and less. There was a case when the son of one of these sympathizers was beaten by the occupiers, and that was the end of his sympathy. You see, after what the invaders did, even those who had sympathy, it turned into disgust for the Russians. Roma as a whole is a very apolitical people, but this whole occupation situation with the destruction and looting of Roma houses simply could not leave the Roma indifferent, even people who did not know anything about Russia, or vice versa, used to often travel to Russia, now they curse and hate the Russian occupiers and everyone who support them.

- You say that Roma are apolitical. Will they change after the war? What do you think?

- They have already changed. Now such a process is taking place, this has never happened before. Wherever the Roma lived: in Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Ukraine, they always considered themselves one people and nothing could be contrary to this. Now this is not entirely true. This military context, the Russian invasion, this tragedy is so strong, so painful, that many Roma have stopped communicating with their compatriots from Russia. Ukrainian Roma people have changed. Many Roma joined the army. Although it was believed that the Roma and the war were things that were not compatible with each other before. That this is not a Roma affair, but a “Gadzhen” (foreign) one. In our town, the Roma used to laugh at the Roma of the military, but now we are all proud of our defenders. Yes, we are proud of the Roma who ended up in the Ukrainian army and defend their land, their family, not only their family personally, but in the broadest sense, the Roma family of Ukraine. We are proud of all the defenders of the Ukrainian people, regardless of ethnic origin.

All this has changed the Roma culture and worldview.

- After the victory, do you think the Ukrainians will forget the Roma?

- I think not. I watch the publications on the Internet. Prior to the Russian invasion, many Ukrainians, without reason, were aggressive towards the Roma. Many of the comments were venomous. Often people hated Roma for no reason. But this is not only in Ukraine, but in any country, in all countries, the Roma have the same problems, approximately. Now I’m looking at publications about Roma and 95 % of the comments are positive, people support the Roma, and it doesn't matter what this publication is about. And I’ll even say more, I see that if someone writes a negative in the direction of the Roma, then people begin to intercede and crush the hater. This has not happened before, and even if it did, it is much less.

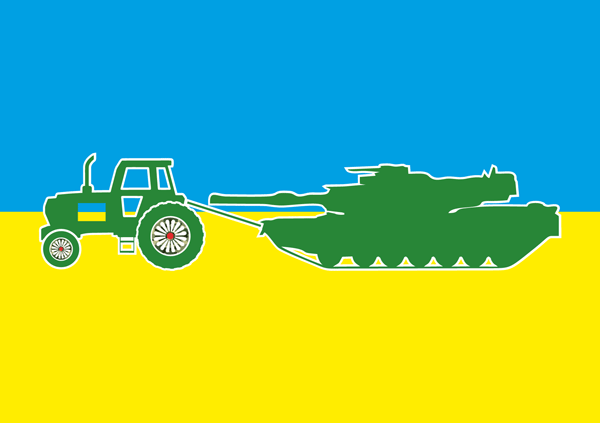

- By the way, I didn’t ask you about the stolen Roma tank. Was it in the Kherson region? Your Roma have made all Ukrainian Roma popular.

- Yes, yes, this case with the tank is very positive for us, it was a “gypsy special operation” (laughs).

You know, when Russia attacked in 2014, annexed Crimea and occupied parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, among the national minorities of Ukraine, the Crimean Tatars were the most in focus, and now in 2022, the Ukrainian Roma. Roma really help and do a lot in this war. Everyone is doing or has done something: helping the army, protecting the country, helping migrants. I practically do not know such Roma families who would not participate in the resistance to Putin’s horde in some way. Now the people of Ukraine are creating their own history and the Roma are part of this history, so we cannot be forgotten in any way. Before the war, we were divided into nationalities, but now it does not matter. We are all Ukrainians and equally we are doing everything possible for the victory of Ukraine, for the preservation of our families. We suffer in the same way, and Russian missiles fly equally at Ukrainian and Roma homes. And children of any nationality cry the same way. Everything is the same. We are all in the same conditions and should help and support each other.

Slava la Ukrainati taj lati narodonendi! (eng. – Glory to Ukraine and its peoples!)

Author: Viktor Chovka

Translation: Anastasiia Tambovtseva

Додати коментар

Коментарі - 0